This is the first part of a three-part essay on The Talos Principle which includes commentary from writers Jonas Kyratzes and Tom Jubert.

“In the beginning were the Words, and the Words made the world. I am the Words. The Words are everything. Where the Words end the world ends. You cannot go forward in an absence of space. Repeat.”

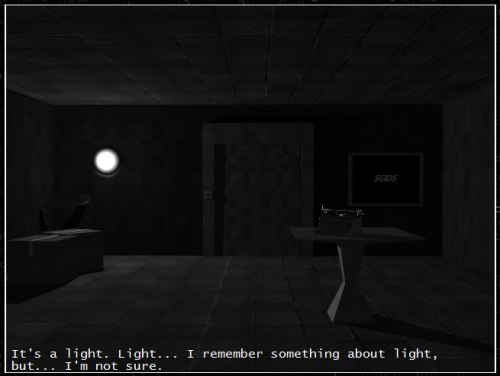

The most glorious moment in The Talos Principle (Croteam, 2014) is one that comes again and again. The moment occurs when a “sigil” is liberated from a devious puzzle, but the sigil itself is an empty token of advancement, the kind of dull trinket that games thrive on. No. The sigil has no power.

Turn around. Don’t speed on to the next challenge, just stop. Turn around and survey the glorious red and blue stitchwork you’ve sewn across the puzzle. Look at this ingenious thing you have made and be proud.

Spoilers for The Infinite Ocean and The Talos Principle follow.

A puzzle game often features hot, sexy brain action that’s tuned so well it’s difficult to thread a story through it. For example, The Swapper (Facepalm Games, 2013) covered unsettling philosophical ground but still came down to “solve puzzle for meaningless number of orbs to unlock meaningless doors”. Portal (Valve, 2007) tore through this and accepted that the puzzles were, uh, actually puzzles, then threw in a black comedy about a testing AI run amok. But in a sense it’s a one-trick pony, right? How many puzzle games that acknowledge “they’re really tests” can you bear?

When I saw the original teaser trailer for The Talos Principle (Croteam, 2014), I first wondered why Serious Sam developer Croteam had made Jonathan Blow’s still-unreleased The Witness. It became even more intriguing when I found out Tom Jubert (Penumbra, The Swapper) and Jonas Kyratzes (The Sea Will Claim Everything, The Infinite Ocean) were on the writing team.

“I got involved because Davor Tomanic, the level designer, enjoyed The Swapper,” explains Jubert. “They basically said to me, ‘Can you do something like that, but with more robots and interactivity.’ The guys at Croteam weren’t interested in just bringing someone onboard who could write a solid story. It was their ambition to produce something which could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the classic sci-fi oeuvre.”

But where did co-writer Kyratzes enter the story? Kyratzes had written a short science fiction point-and-click adventure in 2003 about artificial sentience called The Infinite Ocean. After being encouraged to give it an overhaul, it was re-released in 2010 to much praise. Jubert, a graduate of philosophy, found it irresistible and wrote a two-part essay on its themes and implications. They debated a little in the comments of the piece.

“Deconstructing the philosophy of one of the most intelligent, intricately constructed examples of interactive art available has been a mission and a half.”

When Croteam came knocking, Jubert recalled The Infinite Ocean and suggested Kyratzes as a possible collaborator. “It was all surprisingly simple, actually,” admits Kyratzes. “A few emails were exchanged and then I started writing.”

Croteam provided thematic starting points such as artificial intelligence and humanity. “We pitched a number of story concepts that could deal with those themes,” says Kyratzes, “and also make sense with the puzzles and the parts of the game that had already been developed. Croteam had expressed some interest in a story based on the Garden of Eden – a story I also find fascinating – so this seemed like a natural fit.”

Stripping it down, The Talos Principle is a first-person puzzler in which the player is tasked to negotiate several obstacles to reach a goal. Forcefields, drones, gun turrets and even topography all conspire to thwart you. But Talos is my favourite type of puzzle game, the honest game. I’ve talked about how I adore open kimono puzzle games like Full Bore, Sokobond and The Swapper, where everything you see is enough to solve a puzzle. There are no special upgrades. No power ups. Not even hidden “portalable” surfaces you’re required to spot, which upset me during the Portal 2 (Valve, 2011) single-player campaign.

It’s maddening. Everything is there, in front of your eyes, but you can’t figure it out. Talos keeps finding new ways to convolute the puzzles without simply enlarging the puzzle sizes. What I like about 3D puzzles over 2D is that in most cases it’s difficult to see a puzzle in its entirety, so the player has to do a lot more work to parse the environment. In some rare challenges, you may even need to resort to pen and paper.

There are extra-hard star challenges strewn across the game which do not fall into the same “honest” category. Many stars are hidden or require you to spot that the environment can be used in a certain way; a ledge here, a gap there. They often require you to work across multiple puzzles. Some of these are incredibly satisfying but others, like the original version of the Push It Further star (Level A4) which required the player to spot a connector hidden in a tall tree, leave you slack-jawed, feeling the solution was less brain and more exploratory brawn.

Much of the early game is a tutorial that stretches you to think a little bigger darling, teaching you techniques that need to be reused in many later puzzles. For example, an early lesson is that you only need two jammers to pass through a series of forcefields. Later on, there is also what might be termed the “impossible connector configuration” where you use the power source trapped behind the forcefield to unlock the same forcefield.

But I found the “sigil” Tangram puzzles boring in comparison to spinning webs of light and never acquired a knack for them. I felt like I was wasting my time, jamming shapes into a sigil lock at random again and again until I happened upon the correct configuration.

Also, I feel I speak for many when I say I learnt to dread the appearance of the triangle “play” icon on a puzzle. The recording machine presents a particularly uncomfortable type of challenge, where the player must become familiar with the complicated impacts of playback on the world. Initially it seems these puzzles are about getting a duplicate to do things for you but, if you want to defeat the puzzle on the fifth floor on the tower, it’s vital to understand the recording puzzles are about doubling the components you get to play with.

What makes this worse is that experimenting in the recording puzzles is expensive as you spend a lot of your time recording yourself waiting, and the frustration quickly accumulates. Such puzzles also cross a crucial red line for me, because they can end up becoming arcade sequences where you have to coordinate activities in step with your recorded double. I abhor it when a cerebral game throws an action wrench into the mix.

Yet I must confess that even these most bitterly hated puzzles make me feel astonishingly smart for figuring them out. There’s an artistry, an undeniable purity in Talos’ puzzle design.

Let’s talk about Talos’ biggest problem: the world reset. Sometimes you need to reset a puzzle, having shunted yourself into a no-win state, but the reset is not confined to the puzzle – it wipes the entire world of changes, which is painful if you’re setting up a play for some of the more difficult stars. And if you “die”, there’s no choice in the matter: boom, world reset. I cannot fathom why you couldn’t just be sent back to the start of the puzzle but leave everything intact. The game does a mock rewind of events, making it even more galling that an actual rewind isn’t available; Croteam must surely have considered it.

The incredible puzzle design would have been enough to convince me Talos was one of the greats, but the story work that Kyratzes and Jubert ploughed into the game gives it so much more weight. In one sentence: human race perishes but, in its dying moments, initiates a long-term computer simulation in which it is hoped a sentient intelligence will evolve to carry on the torch of humanity… but the simulation itself is frightened to die.

But it’s much more than that. It’s a story of individuals pulling together to “save the world” and what exactly that means. It’s a story of a species facing the end with dignity. It’s a meditation on what it means to be sentient. It’s a story of programs desperate to understand the strange prison they are born into and the “god” that presides over them. And virtually all of this is told through text, some with a conversational component.

“The overarching structure, web texts and religious themes Jonas definitely took the lead on,” says Jubert. “Though the religious stuff was there in the gameworld already, my initial pitches were rather more… I don’t know what the word is. Less fatalistic, less dramatic, less epic… basically less biblical in every way. The one that sticks in my head was the idea that the simulation was a sort of futuristic Encarta, left to rot away on the internet. It would have been a very different game, and that’s the reason I wanted to bring Jonas onboard – because his writing has an aesthetic and mythological quality that forced me to develop ideas consistent with it which I never would have done in other circumstances.”

Kyratzes took some inspiration from Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. “I wanted it to be a story about synthesis, doubly so because one of the most fascinating aspects of the Eden myth is how it reveals the syncretic aspects of Judeo-Christian mythology and contains so many traces of older belief systems. This is also why I picked the name Elohim; many scholars consider it to be a plural, left over from a time when the religion was polytheistic.”

To be frank, the puzzles are still fundamentally separate from the story, but the glue that tries to patch it all together is damn fine glue. There are three primary modes of storytelling going here: there are direct responses from Elohim, the “god” of The Talos Principle, the QR codes found on the walls and interactions via terminals.

I’m not as much a fan of lore and reading as I used to be, but I’m always up for terminal porn. I love how the Talos terminals operate and react, the little pauses, the clicking, it’s so beautifully tuned. I’m the kind of person who loved the menacing terminal-based opening of the Memory of a Broken Dimension prototype. It’s a matter of personal taste, of course, not everyone could get invested in page after page of reading. At times, even I wasn’t sure if it was all a bit too much.

With two strong writing voices in the mix, it sounds like it would be easy to get lost with regards who was responsible for what. The credits show Kyratzes was responsible for spoken dialogue and static texts on the terminals, whereas Jubert was on the QR codes and interactive sections of the terminals. “While we left each other a great deal of freedom,” says Kyratzes, “naturally there were areas where we had to be on one page, or where commenting on each other’s work was necessary. There was also a lot of preparatory work that we did together, establishing many of the basic parameters of the story and the world. We also had full access to what the other was writing, so we were always reacting to each other in one way or another, making sure it was all consistent.”

Nonetheless, there was something familiar about the setup. An AI navigating a simulated environment, learning more about itself and the outside world through corrupted document fragments on terminals: it felt like a supercharged upgrade of Kyratzes’ The Infinite Ocean.

“I was actually trying really hard to avoid retelling the same story,” he explains, “since I really hate repeating myself, but everything kept evolving into that direction, perhaps partially because Croteam enjoyed The Infinite Ocean. I think some of the mistakes I made in my first few drafts came from trying to avoid similarities. What I ended up deciding was that if The Infinite Ocean is a game about an AI becoming a god, Talos is about an AI becoming human.”

Next: “I could go on but I’m afraid it would get even more pretentious.”

Download my FREE eBook on the collapse of indie game prices an accessible and comprehensive explanation of what has happened to the market.

Sign up for the monthly Electron Dance Newsletter and follow on Twitter!

I’ve not yet played the Talos Principle and I want to. I also want to read this article. How much do you feel I will lose by reading this prior to playing the game?

(I don’t want spoiler warnings per se! I just want to understand the impact of reading analysis before subject. E.g. if Talos Principle explores an interesting perspective gradually over 20 hours, am I going to bore myself if I experience that after reading a neat encapsulation? 🙂

Hi Shaun! I think it will spoiled to be honest because Talos is a mystery which you have slowly figure out. (The expansion is not.) I even have a dusting of mechanical spoilers above which you might not even want to go near, although that’s probably more paranoid on my part.

If you’re not too bothered, you can read down to the paragraph “Let’s talk about Talos’ biggest problem” without getting much story unravelled. But in the paragraph after that (“the incredible puzzle design”) I summarise the whole story in a single sentence!

If you want “the review”: fantastic puzzle game, really great story work (if you’re into lots of reading, that is). Where Portal is a great blockbuster movie, Talos is indie cinema, much more thought-provoking and lingers in the mind.

Thanks Joel! I think I’ll hold back from reading this all together – for now. Hopefully, I’ll play Talos before the year is out.