This is the second article in the Dishonored quadrilogy. The first was Fish Out of Water.

I was getting impatient. The guard was hanging around one of the dull paintings in Dr. Galvani’s collection and I just knew that if I made a move towards him he would decide at that specific moment to turn around. I really didn’t understand this. He was supposed to be patrolling about so he could walk into my choking embrace, after which I would fold his unconscious body away discreetly like fresh laundry.

I swiped a glass off a sideboard and threw it across the room. It shattered against the far wall.

At last, the guard stirred and prised himself away from the painting. He approached the spot where the glass had smashed. I blinked under a table between us, popped up the other side and grabbed his neck. He spent the rest of the evening passed out under the table; out of sight, out of zzzzz.

Yowsers. It’s been a long time since I played Thief.

A love affair with Garrett

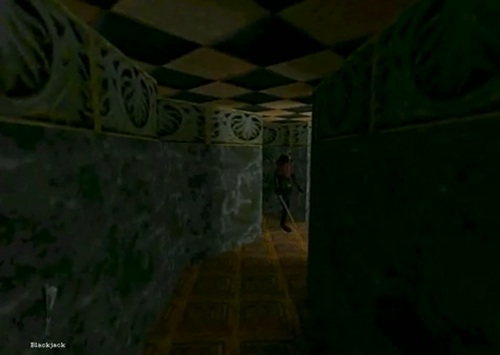

Looking Glass Studios’ stealth game Thief: The Dark Project was a title that did so much right. Thief embraced open, nonlinear level design, which is why it became the seminal first-person sneaking game. But it remains on critics’ desert island lists because it also featured an intelligent fusion of story and action that elevated it beyond a mere experiment in stealth.

The protagonist of Thief was charismatic anti-hero Garrett, a brilliant risk-averse thief who served no master. He stole from the rich, just like Robin Hood, although unlike Robin Hood, he just gave to himself. His sardonic quips suggested a man jaded by history; we knew Garrett but we never really knew him. But we knew he was no killer.

Thief had a great story which was revealed so slowly that players could be fooled on the early missions that it did not even have one. But as Garrett spent so much time in the private spaces of the rich and infamous, Thief was as much about the lives of others as it was about Garrett’s exploits; we learnt more about his victims and their associates than we did about Garrett himself.

The sequel, Thief II: The Metal Age, built upon the successes of Thief. Its high point was a piece of stunning level design called Life of the Party, where Garrett approached the Mechanists’ tower Angelwatch via the rooftops of the city. Shortly after release, though, Looking Glass perished and the final adventure of Garrett was seemingly denied to his fans.

The project was rescued by the studio that created Deus Ex, Ion Storm (Austin), and some of the original Thief team were taken on to develop the final game. The result was Thief: Deadly Shadows, which received a mixed reaction from Thief stalwarts. It was more forgiving of murder, forced the player to spend a lot of time in a frustrating city hub area and carved up mission areas into zones so as to meet console requirements. It even dumped the beloved briefing cut scenes. Nonetheless, all were grateful that Garrett’s story was completed.

Despite the critical accolades, Looking Glass went under and stealth is a tricky proposition for a developer. There are two design problems associated with stealth gameplay.

- You do a lot of waiting and watching. Then maybe some more waiting.

Stealth has always required patience from its players. Thief rewarded this patience with involving storytelling and a world that seemed fresh compared to what else was on offer. One of the lessons the mainstream industry took away from Thief was that stealth can be fun but stealth must not be the whole story.

- Getting spotted means quickload.

With FPS games, we have a health meter which is essentially an error tolerance bar; players can screw up some but not too much. In stealth, there is no equivalent. Once opponents have seen you, this makes further stealth close to impossible and so stealth enthusiasts have a finger trained to jab the quickload key. Some stealth scenarios even terminate immediately upon exposure.

The traditional response to both these concerns is to tolerate stealth error; players are permitted to make use of weapons to murder their pursuers if all else fails. However this quickly billows into a game of two halves: some players dedicate themselves to a non-lethal ghosting approach while others like to play assassin in the shadows.

Stealth game developers are thus catapulted into an RPG model where they have to contend with multiple play styles. More choice means more overhead and so stealth mechanics may not get the love they deserve. Consider the original Deus Ex which sported stealth but backed it up with plenty of powerful weaponry; stealth was meant to be used as one of many player tools but it wasn’t a goal in and of itself.

So no stealth experience ever felt as clean to me as the first two Thief outings.

Until I played Dishonored.

Thief IV: Mirror’s Edge

Dishonored is:

- Life of the Party all of the time, soaring across rooftops, looking down at the troubled people of the city, feeling safe… and supreme.

- Parkour-style Thief, where the blink ability confers a sense of spatial power making the environment yours to command.

- An epic patchwork of fictional lives. From the Overseers who are losing their religion to the parents who watch their children perish from plague. From the unappreciated and mouthy Lydia in the Hound Pits Pub to the aristocracy who fiddle while Dunwall is burning.

- A game where Thief’s signature mechanic of hiding in shadow has been swapped out for a cover system that really works. It’s gorgeously solid.

- A series of stealth puzzles that rise in complexity, where the non-lethal addict will sometimes be forced to stop and think, searching for a solution.

- A handful of missions criss-crossed with oodles of optional sidequests and secret stashes. An exquisite feast for explorer-players who will disable objective markers the first chance they get.

There are so many beautiful touches to this game that I could spend paragraphs just documenting them all. I love the relatively minor addition of keyhole peeping which gives the player more control over their game. Despite my complaints regarding tutorializing last week, Dishonored keeps a lot of its tricks close to its chest. You can hide inside fireplaces and under tables, for example, which was a big surprise when I accidentally discovered this. And the developers do not spell out what the limited “possession” ability is useful for; it is down to the player to spin this into an advantage.

I’m also comfortable with some of the trade-offs it makes between realism and playability. Guards will not react to certain discrepancies in their environment, such as all of their colleagues disappearing one by one… although they sometimes notice.

But let’s address a disconcerting disconnect between Thief and Dishonored. Many of the missions are out-and-out assassinations, which is clearly not a Thief trait and does not sound very non-lethal. Dishonored pays attention to murder and tracks deaths due to your presence, so the developer offers eco-friendly alternatives to all of the assassinations, some obvious and some… not so obvious. I would caution anyone thinking these are analogous to choke versus backstab; no, no, the non-lethal alternatives are generally pretty horrifying. Even the relatively harmless alternative to murdering the High Overseer in the first real mission has a sting in the tail, revealed much later during an optional sidequest.

There is one point where the game compromises the stealthy player in a major way; the player is ambushed by several magical assassins, meaning a fight is almost guaranteed. This only makes sense if you think the player will diversify and use all the tools at his or her disposal. Most of the stealthphiles, however, will simply quickload the ambush out of their game.

Still, impatience often kills me, trap or no trap. I remember legging it up the stairs in The Captain’s Chair hotel only to discover a pack of flesh-eating rats at the top of the stairs. If there’s one thing in Dishonored that gets the adrenaline flowing, it’s a pack of hungry rats.

But time for the negatives. Dishonored fails to live up to the Thief lineage in several ways.

The Weaponized Garrett

I’ve not really touched on the story of Dishonored so far and that’s because I will get into that in the next instalment. In brief, Corvo is not Garrett. Instead of Garrett’s cynical asides, we have Gordon Thief Freeman, a virtual mute who is meant to embody the player. This means any narrative comparison with Thief is likely to come off badly, but it goes deeper that that.

Consider the slow-drip story of the original Thief, where the main plot doesn’t really show itself until the fifth mission and even then it isn’t apparent to a first-time player. In Dishonored, everyone is obsessed with assassination from day one and Corvo is the most important person in this pocket universe. Everything is super-urgent. Garrett is vulnerable; Corvo is a familiar power fantasy.

I also wished Dishonored made more of an effort with its lore interface. Whenever Corvo reads a document, it looks like I’m reading a text file on a modern computer, not one of Admiral Havelock’s hand-written journal entries. Thief at least mocked up something that befitted the world to maintain immersion.

Nonetheless, the real reason why Corvo is not Garrett is because he walks around with a knife out all the time. Corvo just loves his knife, he’s probably given it a name like Little Corvo or something. No matter how many times I tuck it away, Corvo just likes to pop it out any chance he gets. Time to blink across the rooftops – hey, lady, have you seen my awesome knife? Excuse me while I whip this out–

As a passionate advocate for a non-lethal way of life, this is one thing I just can’t get used to. Corvo can never replace Garrett in my heart.

Thief forever and always.

Download my FREE eBook on the collapse of indie game prices an accessible and comprehensive explanation of what has happened to the market.

Sign up for the monthly Electron Dance Newsletter and follow on Twitter!

Blink is at the core of the mechanical differences to Thief. You’re right to call out its sense of power. On the one hand, it’s like Thief’s rope arrows: a way to traverse space with freedom, escaping from the two-dimensional tyranny of walls and floors; only much moreso, because Blink works anywhere and everywhere, not just where there happens to be wood—and also instantly,

On the other hand, because of its power Blink bypasses so many of the normal stealth challenges that it comes close to (if it doesn’t quite achieve) a near erasure of the tensions of stealth play. Spotted by a guard? Just blink away, and he’ll lose you. Guard wont move away from his post? Blink behind him. Can’t reach that ledge without traversing a treacherous pool of light? Just blink to it. In this way, Blink is detrimental to stealth gameplay just as that its distant cousin, fast travel, is to exploration.

I love how you referred to the guards’ “colleagues.” That is all.

I don’t mean that’s all I loved about the piece. Far from it. Just, that’s the only constructive (?) thing I had to say. Ok I’m leaving.

@Karras

I mean @Andy

Yep, the blink switches it from creeping Thief to parkour Thief. At first I thought blink was a gimmick, but quickly I found it was an explorer’s boon. I found myself quite comfortable with Dishonored’s alternative take on stealth.

I hadn’t twigged that it probably depressed some of the tension of stealth; it could be I wasn’t using it as aggressively as it could be. Certainly I probably used it to “cheat” through some stealth situations, but I recall more the moments of sheer terror knowing a guard was coming around the corner, desperately trying to get the blink indicator to “lock” to a higher ledge.

I’ve noticed the more you play Dishonored, the more you talk about it, the more optimal your play becomes. There are so many little tricks that don’t come to mind on a first pass. Maybe if I played some more, I would have become more refined at blink – and effortlessly eliminated all of the stealth challenge. Hmmm.

I’m still wondering how the official Thief IV is going to turn out. Part of me feels like Dishonored is to Thief IV what XCOM was to Xenonauts.

@Alex

Thanks! I will use the word colleague as often as I can in future.

@HM – You’re right about learning the breadth (and sometimes depth) of the player tools available the more you play. I played it straight through three times in a row, and it was on the second run that I was learning to be very efficient with Blink, because I was ghosting. I was definitely describing the later effects of Blink, rather than the player’s first-time experience with it.

What struck me the most (and some others I’ve read) is the strong mechanics advantage given to killing over stealth.

Most of the purchasable items, tools, skills, and bone charms are very specific to lethal combat. I ghosted every level of Dishonored because I enjoyed that challenge. And Dishonored certainly did deliberately permit the sneaky Thief-like play style — the end-of-level scoreboard showed that the game was watching whether you killed. But by the game’s end it was very clear which of the two approaches Arkane wanted to encourage.

That’s not necessarily a flaw. Arkane had to know their game was going to be compared to Thief. So designing Dishonored to make Corvo less Garrett-like by offering a lot more murdery mechanics could have been a conscious choice by Colantonio/Smith/et al.

On balance, Dishonored might have been more fun for those of us who enjoyed Thief had it made the mechanics more balanced between killing and sneaking. But then it would have been a Thief game, and not a Dishonored game.

This post also helps explain why I think I was left underwhelmed by Dishonored. My playthrough was essentially a “rat run” in which I would loudly announce my presence at the beginning of each level, spawn rats, and run into an alley. Then, I’d just sit back and watch the show (well, sometimes I’d help the rats out, but most of the time they didn’t need much help). The rat swarm is so cool but so overpowered! It seems I have completely exhausted my capacity for patience (perhaps by gorging on short-form fair, which you’ve written about). Or maybe I never had this kind of patience to begin with because I never cultivated it by playing games like Thief. Back in the day, I played a lot of JRPGS. One would think getting all the way through one of those would cultivate patience, but then repetitive grinding is probably closer to laziness than patience. Now your post is making me think that I’m not giving triple-A games enough of a chance because they tend to introduce themselves so poorly. Hmmmm

Okay I am commenting from Heathrow airport. Flight departs in a couple of hours…

@Andy

I am almost done with a second playthrough that embraces violence. Expect to hear more about this later. It’s a lot quicker because I know the levels, know my skills better… and, of course, using murder a lot more.

@Bart

I’ve tried to organise my Dishonored ramblings into categories. Last week was AAA handholding, this week is Thief IV. I’m definiely coming back to combat-based play later.

It is true that there are a lot more tricks available for the amoral player (turning wall of light or arc pylons into weapons, or turning on the spotlights on the apartments) but playing through those later levels as a stealth-enthusiast is enormously satsifying.

There’s only so much that can be tested with a game that encourages such an open playstyle and I was pleased to see there was far less “this here is your stealth route” signposting that I expected. Perhaps that does mean Arkane was slanted towards the hybrid play- but on the upside, it meant stealth fanatics had an awesome time a la “Into The Black”.

@Alex

Yeah, playing Dishonored is a direct consequence of last year’s “Rehabilitation”. I think I spent something like 30 hours on my original playthrough. I was determined to do it properly – and Dishonored let me do this. It didn’t prod me too much to “hurry up” and get on with the main missions.

I think Mrs. HM was a little quicker, but then I helped her out with a couple of the bits that are difficult to work through without objective markers.

I haven’t got the rat swarm power but, in violent mode, I have herded an existing swarm into a fight. Rats vs three members of Slackjaw’s crew? The rats lost.

There’s another reason why Dishonored is a poor Thief (and stealth) game: it completely eliminates the hunting phase.

If you’re ghosting then I suppose it wouldn’t matter, but for mainstream Thief players being hunted by guards is the tensest and most challenging stage of the game. As Mr. Yang puts it:

The hunting phase in Dishonored consists of a suspicious guard standing completely still as a HUD element over his head fills up. Evasion as a player typically consists of heading back around the corner you just turned (or “cheating” with Blink, as Andy pointed out). It’s depressing.

@Tom: Yes. In Thief, unless you were trying not to be seen at all, the level design tended to encourage you not just to quickload when you were noticed – you often stood a chance if you ran away, found a shadowy area and hoped they wouldn’t spot you after that. It provided some of the tensest moments in the games, and you could sometimes even turn it to your advantage if, as the guard gave up and headed back to his post, you could get round behind him and bop him on the head. The blackjack has to be one of the most satisfying weapons to use in any game.

Also you get the comedic panic when you sneak up behind a guard, bop him on the head and get the metallic sound indicating he’s wearing a helmet that’s proof against the blackjack. All you’ve done is let him know you’re standing right behind him and it degenerates into a Benny Hill style chase sequence.

One of the things that always got me with Thief was that while Garrett frowned on killing – not out of any moral sense but because he considered murder tacky, careless, and beneath a master of his caliber – an arrow (or sword) from the darkness would kill in one hit. Sometimes, despite my love of the stealth elements, I couldn’t resist putting a broadhead into a guard’s neck from the shadows.

In capturing much of Thief’s essence, Arkane recognized the subtle things that made Thief what it was: the City, and Garrett’s equipment, were “characters” just as much as he was, for example. Distinctly lacking, and a shortcoming in Dishonored, is Corvo’s silence. Garrett’s personality was part of the game experience in Thief, and I think Arkane did their game a slight disservice in the way they handled Corvo Freeman. This idea that we project ourselves onto the protagonist is an okay concept from a design perspective, but in a story-driven narrative you need defined characters, not ciphers.

I look forward to more installments!

There’s one other important distinction between Thief and Dishonored: Garrett could alter his world.

A big part of Thief (and a typical Looking Glass motif) was that the world itself was interactive. As Garrett, you could douse some lights, or muffle flooring. It wasn’t a lot, but it did give you more tactical options for up-close stealthy play versus guards.

While the architecture of Dunwall definitely helped with creating an immersive world, it was just there to look at. You could pull batteries out of fences/towers, but that seemed to be more about encouraging players to try alternate routes through a level rather than having more verbs directly related to the core gameplay mechanic as in Thief.

One other hint about this difference was that guards in Thief would complain if a torch suddenly went out near them… but I don’t recall any NPCs in Dishonored complaining that a fence or tower inexplicably failed.

Again, this isn’t to bash Dishonored, a game I enjoyed. I think Arkane was just being careful not to copy Thief. And I suspect that was the right choice… but it does leave me looking forward to Thief 4. 😉

I want to respond to all your comments but still in NY for IndieCade and a little hungover. If I type too loudly, it will awake Richard Hofmeier who is sleeping like a man-baby on the sofa a few metres behind me.

Possible responses:

…Friend-zoned?

…Up all night HM?

…So you’ve been exploring… games, right?

…Addendum: No homo

…I will not dignify this low-hanging fruit with a dirty-minded response in such a dignified place. Nor will I besmirch the names of those people I scarcely know and have never met.

I just don’t know which one to go with, so I’ve just spewed them all.

No idea how I missed this. Been in a lot of rabbit holes these days…

I like your observations on stealth in general. The attitude of reloading especially. That’s something only stealth inspires in me. I’ve found myself reloading even while playing Ghost Recon Future Soldier, because there are secondary stealth objectives (I try to go through with the highest ‘ghost rating’ possible). I’m not bothered if I miss other optional objectives, but the stealth ones, I have to have those.

Stealth is a wonderful mechanic (for lack of a better word) and although I love Thief as well, I’m wondering if you’ll be pulling from other examples to compare/contrast with Dishonored. Looking forward to the next piece.

@Tom

Hi Tom! I agree with a caveat. Unless you’re replaying Dishonored or, perhaps, pretty good at picking it up, I don’t know if these issues are that problematic. I had plenty of times where I was trapped or couldn’t climb out of harm’s way fast enough. Often when I was blinking around like mad I inevitably reloaded. Dishonored does not do well in the replay stakes, but I had enormous fun on my initial 30-hour playthrough. It was possible to convince myself I was playing Thief.

@Phlebas

Welcome back to the comments! I wonder if what something that’s missing versus Thief is the visibility. With Thief, you were in shadow and could see who was hunting you as they approached. In Dishonored, you’re inevitably hiding and unable to see your pursuer and it becomes a game of audio. I remember the one time I looked through a keyhole and freaked out as a guard was about to open the door from the other side. But you definitely do not feel as vulnerable as you did in Thief.

@Bart

At first I was going to disagree but thinking it over, you’re spot on. Garrett has more environmental action than Attano. Yes there are doors and the occasional switches (and candles!) but he couldn’t do something like “make cover”. I would take issue with the guards noticing torches being out, I felt like this didn’t make too much an impact in the Thief (they didn’t start searching for you) and I’ve noticed a similar thing happens in Dishonored too. Guards do *occasionally* notice their brethren have disappeared and assume they’ve skipped duty. The guards are also wise to a wall of light or arc pylon being rewired because if they see others get atomised they will not do the same thing. In fact, pylons aren’t that safe because they start throwing things at you from outside the radius. Dishonored’s reflection on environment is different to Thief, but there are some special touches in there.

@Steerpike: But when you killed a guard, you immediately reloaded, right? I do that all the time in Dishonored as well – which lead to a interesting story I’ll reveal in the third Dishonored article.

@mwm: I guess you’ll just have to wait until the second part of “The High Five” goes live.

@Jordan: In general, Jordan, the series covers these topics in order: AAA handholding, Dishonored vs Thief, what Dishonored is and, finally, violence in Dishonored. I’m done with the Thief comparisons for now but willing to entertain discussion in the comments!