Laura Michet’s candidate for the 2010 Most Unlikely Gaming Blog Post award over on Second Person Shooter put forward the concept of a “gamework”, the vector composition of surface and latent symbolism, using ideas from the work of Sigmund Freud. It got me thinking, as you might expect.

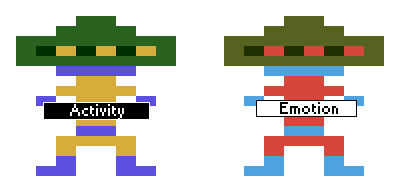

I agreed that I also saw a game as a composition of different elements, although I admit that I couldn’t quite embrace Laura’s gamework. The decomposition I was more content with was pretty simplistic, crude really. I saw games as a combination of a (Lewis Denby-despised) gameplay core coated in a glossy emotional paint.

Trine, for example, is impossible to discuss without commenting on its beauty, but this has nothing to do with the actual gaming activity you’ve bought. VVVVVV demands you refer to its throwback eighties platformer chic, which is separate from its simple gravity-flipping mechanic. Lost Planet forces you to stick two fingers down your gut and compare what emerges with the game.

And thus I saw this:

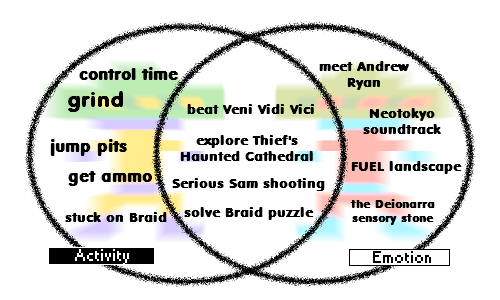

I thought some more and realised that activity and emotion are not distinct robot characters from a computer game I wrote in 1995. We needed our old friend the Venn diagram to get to the bottom of this pretentious pontificating.

I toyed with the idea that it would be better to maximise as much of the activity to fall within emotional space; after all, there’s no point engaging in an game activity that does not provoke an emotional response. It’s supposed to be fun.

But what if the activity is reduced so as to become a very small part of the experience? What do we call something where the emotional content outranks the actual game? (Bonus points for members of the audience that shouted out “Metal Gear Solid”)

If interactivity is de-emphasized, that sounds more like a story where your control, your participation is merely how quickly you turn the pages. Ah… these are the indie art games.

Jason Rohrer’s Passage has little interactivity, as cruelly exploited by Passage In 10 Seconds; the point of the game is the emotional payoff at its end. Dungeon by Jonathan Söderström (‘Cactus’) and Arthur Lee pretends to be about the activity, but is more about what the activity does to you. Molleindustria’s Every Day I Dream The Same Dream is a simple graphical adventure, without real challenge – you “win” by doing what you’re not supposed to do, refusing to comply with social norms and the rules of the system. And then there’s Daniel Benmergui’s puzzle-poem of Today I Die.

Are these games at all? They are far from your conventional game – what Michael Samyn of Tale of Tales considers “tests”, challenges to best. These games don’t actually want to defeat you, unless their point is enforced failure (Dessgeega’s Mighty Jill Off, Noonat’s Queens). They inhabit the same game space: you’re not really there to interact, but to be steered through an experience. You are meant to feel something through the language of this sometimes uncertain medium so that when you eventually release your mouse grip, you are changed. It’s a lofty, but divisive goal.

There are disgruntled gamers that aren’t interested in these anti-games. They understand that you put 10p into a Defender coin-op to hear it growl at you and put sweat in your palms and raise your heartbeat because this is the most fearsome arcade game you will ever face; you don’t insert a coin to play a recorded message, the same message every time, dreaming the same dream. The most recent demonstration of this was the kerfuffle over Jim Sterling’s crude attack on art games, which won him the hearts of this disaffected, hardcore audience. The ranting from the traditional hardliners made it sound like “real games” are under threat; this is not actually true.

It strikes me that this is the same as the “modern art” debate; is Tracey Emin’s unmade bed art? It’s a personal thing: if it makes you feel something, it’s art. If it doesn’t, then it isn’t. Whoa there, hold on now, this isn’t another one of those articles about Games Are Art. The question is whether an “art game” is a game.

I played Passage, it made me sadface; I never felt the need to play it again. I played Dungeon and thought it was an utter waste of my time. But I look upon these works and see them as a new language evolving. I don’t want the “Citizen Kane” of games, which encourages us to crank out more mainstream titles that are B-movie films rendered in uncanny valley 3D, using gaming challenges to fill the plot holes. I want the surreal intelligence of Adam Curtis’ “It Felt Like a Kiss”, I want the complex strata of “The Wire”, I want something that shows me ideas – fictional or real-world – that I hadn’t thought of before. These are the anti-games I want.

Download my FREE eBook on the collapse of indie game prices an accessible and comprehensive explanation of what has happened to the market.

Sign up for the monthly Electron Dance Newsletter and follow on Twitter!

This write-up sort of put all the pieces of this topic I’ve been mulling over this past week into place for me, but it’s something I’ve been thinking about for a long time. I think the issue with these particular indie games is that they really only contrive a certain experience, with one emotional goal. What I hypothesise would be a better aim, would be to create a game that was ambiguous in its motives, meaning that they player derived their own importance from the experience ie the fear of the dark, the sudden crushing realisation that games have told us that killing is the first, and most useful response etc.

Stick around, I’ll write about this. It’s about time I actually did something with Lil’ Pretentious Indie Horror Game the Game, anyway.

Hello Miles. I’m stuck between liking and disliking the art game movement. I feel underwhelmed with most of the art game experiences but also strangely excited within my loins about what the future will bring. These are early days. I *did* get something from Passage, Every Day I Dream The Same Dream and Judith.

But I feel uncomfortable in tagging them as “games” they’re more pieces of art than anything else. I have yet to try The Path, which by all accounts is a much broader experience than the short one-slug art games.

I’ll look out for your fatter set of words on this subject…

The Path was pretty bad. I have no hesitations in saying that.

The problem is that it tried to combine a pretty pretentious and incredibly vague story with a massive collect-o-fest. Although, I do find their concept with the Graveyard hilarious, how buying the game only adds the chance that the old lady might suddenly die.

I would really like to know what goes on inside their heads.

Well, The Path was downloaded onto my drive some time ago. One of these days it’ll get installed and I’ll run my mouse through it.