This is the seventh article in the Where We Came From series.

Toronto, 1982. Peter Liepa, having never written a computer game before, reached out to a local game publisher asking for what kind of ideas might be in vogue. The publisher put him in touch with another programmer, Chris Gray, who had built a game prototype in Atari Basic. It shared some similarities with the arcade game The Pit (Centuri, 1982), in which the player is sent to retrieve jewels from an underground cavern filled with dirt and rocks.

Liepa took on the job of converting it to machine language but felt the game was not compelling enough, so he began pushing the concept in directions he found more interesting. It soon became apparent Gray and Liepa were pursuing divergent design goals and their collaboration broke down to the point where lawyers were eventually needed to resolve ownership of the final product.

The game that emerged from this curious process was Boulder Dash. While the title screen bears the credit “By Peter Liepa with Chris Gray”, it is essentially Liepa’s game with only a passing resemblance to the original prototype. Nonetheless, without the seed of Gray’s contribution, Liepa would never have made this particular game at all.

First Star Software (FSS) released Boulder Dash in 1984. FSS had already caught the Atari public’s attention with previous releases such as Astro Chase and Flip’n’Flop. These games have not weathered the years well, but those familiar with Boulder Dash still speak highly of it.

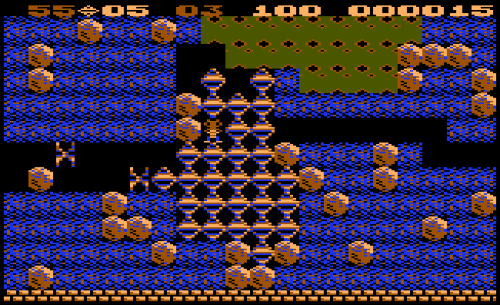

Boulder Dash is one of the finest and most timeless games of the 8-bit Atari’s reign. Clever and challenging, it is a puzzle game sealed in an action shell.

The Physics of 1984

The player assumes control of a small character called Rockford whose task is straightforward yet perilous. Racing against the clock, Rockford digs for diamonds while negotiating boulders and other obstacles. It’s a game where your only verbs are dash, dig and push. There are no guns. But there is death. Oh yes, there is much death.

While digging mechanics had already been explored in arcade games such as Mr. Do! (Universal, 1982), Dig Dug (Namco, 1982) and The Pit, Rockford exists in a much richer, more dynamic world. Boulder Dash is all about the physics.

Most levels are crammed with boulders and diamonds which fall if the player clears out the dirt beneath them. But the physics are a more complicated than “everything hurtles downwards” as boulders will roll off walls and other boulders. A new player soon learns that one false dig will earn Rockford a boulder or ten on his head. Or worse: a diamond which not just kills Rockford but makes the player feel stupid for being so damn greedy. Not every diamond needs to be collected.

Rockford is not alone in this diamond-studded underworld. The natural inhabitants of these caves are fireflies and butterflies which, despite their innocuous names, will obliterate Rockford on contact. But Boulder Dash transforms them from mere hazards into tools to be used to solve a Boulder Dash “puzzle”. When a firefly is killed by a falling boulder, it will explode – a facet that can be used to break through walls. When a butterfly is killed, it explodes into diamonds.

Then there are enchanted walls that look like any other wall until a boulder falls through them and becomes a diamond. As an enchanted wall will only run for a short time, levels featuring them are all about planning and organisation, with the player trying to set up a large drop of boulders to maximise diamond turnover.

But the craziest idea in Boulder Dash is the amoeba, which does nothing but grow. Once it reaches critical size, it will die and harden into a dense constellation of worthless boulders. But the amoeba is a wild beast that Rockford needs to tame. If the player succeeds in trapping the amoeba before it grows too large, it will transform into diamonds instead.

Conquering the raucous, bubbling amoeba is perhaps Boulder Dash’s defining moment. Although the very silence of victory is empowering, the moment is laced with poison – in the silence, the player quickly remembers that time is running out. Many a player has fallen after the amoeba has crystallised, either because they ran out of time or were killed by their own reckless, time-conscious hand. Wading through a sea of diamonds that’s buried under rock is one of the most dangerous things the player can do.

Put all this together and Boulder Dash is the perfect recipe for complex puzzles with emergent solutions. On completing a Boulder Dash level, a player will have found a solution, rather than the solution. At its heart, the game is a creative experience, enabling players to cut personalised solutions out of a dirt puzzle canvas.

Foot Tapping

The game doesn’t offer the greatest graphics ever seen on the Atari but its execution is exemplary.

It starts with the iconic Boulder Dash theme, composed by Liepa himself, which has spawned remixes and remixes and remixes over the years. The rest of the audio also received plenty of TLC as the sound effects are both evocative and fitting. The triumphant snare when the exit snaps open; the glass-like tinkling as one level dissolves into the next; the fading rumble of a recent explosion, particularly affecting if said explosion killed Rockford.

Rockford also had personality. Rockford blinks and taps his foot when he’s idle and, the first time players saw this, they smiled. Unfortunately, this was a trick repeated ad nauseum in many other games. But Rockford’s impassive stare means he doesn’t give off the same snotty, impatient vibe that more detailed characters do when idling, such as Sonic the Hedgehog.

Unusually, the pressure of time is vital to Boulder Dash’s success for two reasons. First, it coaxes the player into making mistakes which, in turn, forces desperate replanning. Second, there’s a strategic tug-of-war between how much time can be devoted to set-up and how much to following through, particularly acute in an enchanted wall level. The time limit is a fundamental driver of player creativity much like speed chess produces games vastly different to tournament play.

The game is littered with subtleties that emerge over protracted play. For example, fireflies and butterflies move in an entirely predictable fashion – but completely opposite to each other. There is also a level devoted to the question of what happens when the green amoeba meets these creatures.

As with all old games, a proclivity for randomness can upset things. The amoeba can sometimes grow too slowly and other times too fast, each case rendering a level impossible to complete. Plus the design decision to make enchanted walls camouflaged means players are forced to waste a life just trying to find them; hidden information in puzzles with time constraints and finite lives tends to be a frustrating mix. However, the reality is that few levels are possible to complete on first pass, due to the necessary evolution of player strategy over several deaths.

In this light, the design choice to only allow certain levels to be selected from the title screen seems dubious. But this was not a crime unique to Boulder Dash as Eighties gaming was obsessed with repetition and artificial difficulty, the unfortunate legacy of the coin-op age.

The controller also feels sticky and while modern players may loathe the lacklustre reactions afforded Rockford, it can be argued that unreliable controls give birth to creative player strategy (take note of Douglas Wilson’s work on the positive aspects of deliberately broken games). Players must plan to minimise reaction-dependent play and develop boulder configurations that are more automated in operation, reducing risk.

None of these aspects are serious enough to wound Boulder Dash. The concept is as playable now as it was 30 years ago and it’s been on practically every platform. Apple II. Sharp MZ. ZX Spectrum. Commodore 64. PC. MSX. Amstrad. Amiga. Atari ST. Game Boy. NES. Game Boy Advance. PSP. Nintendo DS. It has even been in the arcades (several times) and on the iPhone. Many of these versions retain Liepa’s original score as well as his levels.

Yet another new version, Boulder Dash XL, is due out soon for PC and XBox.

We Never Missed You

Two sequels followed on the Atari. Boulder Dash II (FSS, 1985) introduced two new features that Liepa devised: growing walls that expand horizontally and blue slime, viscous material that slows the fall of boulders and diamonds. These were just tweaks to a successful model and didn’t revolutionise the gameplay.

Boulder Dash Construction Kit (FSS, 1986) was a level editor which created an underground trade in custom Boulder Dash levels that continues to this day. This kept the spirit of the game alive for many years even though no more Boulder Dash games were forthcoming on the Atari platform, aside from a port of the arcade Rockford (Arcadia Systems, 1988), a rather distant relation of the Liepa’s abstract original.

Yet despite such strong heritage, it is difficult to identify Boulder Dash’s impact on gaming history aside from giving birth to a crowded field of similar rocks’n’gems action-puzzlers. One problem is that even official continuations of the Boulder Dash series have found it difficult to expand the concept beyond Liepa’s template in a coherent fashion.

It’s been characterised as a highly narrow experience where the game can be given a modern skin but little else. This has diminished its power to inspire as Boulder Dash now just looks like some average rocks’n’gems game – rather than the definitive one. Boulder Dash is Sokoban: most gamers have played some sort of a Boulder Dash clone at one time or another, yet the only thing that distinguishes them are the special effects.

But, perhaps, the most astonishing thing of all is that the creator of the Boulder Dash formula never made another game. Liepa had little involvement with Boulder Dash Construction Kit and none at all with all subsequent iterations of the game. His game career, after one major success, ended.

To find out why, come back tomorrow for the Electron Dance interview with Peter Liepa.

“Looking back, my core interest has always been mathematics and visuals. So there are lots of ways to pursue that, gaming being only one. Perhaps what was holding me back from joining the gaming industry in the long term was that I was not particularly interested in playing games.”

Download my FREE eBook on the collapse of indie game prices an accessible and comprehensive explanation of what has happened to the market.

Sign up for the monthly Electron Dance Newsletter and follow on Twitter!

The best game ever! Were created many clones of this game, but the original version, for me, is the best of all. Great article.

Searching the web I found a clone very faithful to the original Atari Boulder Dash:

http://www.mysteriouslab.com/boulder-dash.php

It’s pretty good

That’s really good although I fear it may be taken down – First Star are still pretty active with the IP. I also love the updated Montezuma’s Revenge also available on the site! Thanks for that. Do you know much about the developer? Details are pretty scant on the site.

There is an Android version called Boulder Dash The Collection. For more info look here:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.firststarsoftware.bdtc

Sasa, I find it amazing you still have to license the Boulder Dash name and everything. I see all that trademarking info at the bottom of your page.

We work together with First Star Software and include the original graphics, music and levels/caves from 1984 😉