A recent addition to the indie sub-basement was an unassuming title called Intra System: Trust Issues (Smoke Some Frogs, 2017). Now I’m not here to announce this is some remarkable sleeper hit, something that deserves to be a major headliner.

What I can tell you is that it’s pay-what-you-want and peculiar enough to hold my interest. It’s a souped-up branching narrative adventure with voice acting. It has you direct a stranger through a series of rooms which may or may not be death traps. It has an interesting twist which I’d like to talk about in terms of narrative game design.

I’m going to be talking spoilers. If you want to have a dabble first, it only takes about 15-30 minutes to get through the whole thing although you may choose to replay.

For everyone else, read on.

THE FIRST TIME

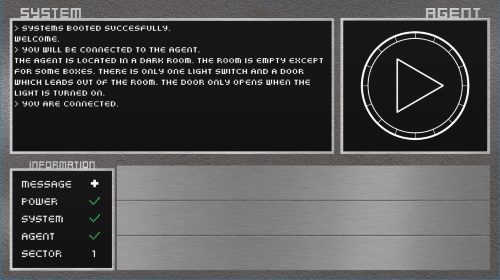

Intra System explains nothing. You see a monochrome console boot up but then it’s down to you. Figuring out the interface is not rocket science, but finding answers is.

Through the console, you interact with a stranger who you can give instructions to. He’s not a simulacrum for the player, he’s a separate individual that the console refers to as “the agent”. He may refuse to follow your suggestions. Neither of you know what is going on. The title of the game suggests there may be issues with trust between you.

In fact, Intra System throws a spanner in the works fairly early if you have the agent search the first room. He’ll discover someone has scrawled the message “NO TRUST”. The agent gets worked up about this later but in the end nothing comes of it.

Admittedly, the whole “trust” thing feels a little bit of a non-event. Generally, I wanted the agent to trust me and I acted in a way that promoted that trust. If you discourage trust, by coaxing the agent into harm, then pretty quickly the agent stops listening to you and the game ends.

Except it’s not just about you and the agent. There’s a third component: the console. It doesn’t just feed you information about the agent’s location, it tells you what to do. Do you trust the console?

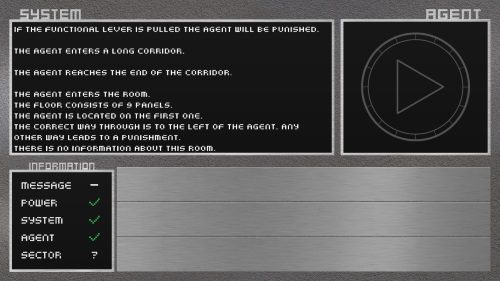

This comes to a head with the syringe decision. In one room, there’s a syringe and the console tells you that the agent must inject themselves with it. It doesn’t tell you why. It just says the agent should do this. Do you tell the agent to inject themselves? You don’t know what’s in the syringe. The agent doesn’t know what’s in the syringe.

Holy shit, this moment.

If you’ve played, you know what happens. The correct decision is to convince the agent to inject, because it is an antidote to the poison gas in the next room. It is perhaps a little surprising that getting the agent to do this is not difficult – if someone asked me to inject myself with an unknown substance, I’d tell them to go screw themselves.

After this point, I felt I had to trust the console although I was never quite sure if it was going to feed me a lie at a critical point. It never did and the worst that happened was the console would glitch. Although I was convinced the console was trying to dissuade me from gathering information. If you encourage the agent to look around, he can find notes and documents that shed some light on your plight.

On my first playthrough, I got the agent right to the end. He shut down the system and found “me”. It was clear that something had been done to me, but… what? Why? What was the purpose of all this? The information the agent had gathered clarified nothing.

The story felt incomplete. I had to run through it again. And it is through the act of replaying that you’ll discover something of a horrifying truth.

THE OTHER TIMES

While that first playthrough was full of tension I knew a second playthrough would have none. The game wasn’t randomized, the voice was the same, the responses were the same… I was no longer dealing with a person. I was dealing with a predictable game. A predictable system. Who gives a shit about trust issues when you’re playing the same game over and over, trying to dig out narrative branches you’d missed first time?

I threw the agent into harm’s way, trying to tease more information out of Intra System. In one room, if you direct the agent to pull the wrong lever, he gets his hand sliced open. On a subsequent playthrough, I had him do it again and the lever broke. Huh, I thought, there is a random component?

Then I played again. And the lever was already broken.

What.

Think about that. I broke the lever in one game and it remained broken in the next game.

That means… every playthrough was real.

Each time you play, the system spawns another agent. You are forced to direct the agent through the same rooms and corridors again and again and again. And with each play, your empathy for the agent crumbles a little more. You make him fail, because failure might teach you more about this prison and yourself. Even breaking the lever uncovers more evidence about what is going on.

You know the agent doesn’t matter. You know a new agent is going to be spawned. And you’ll keep killing them in a desperate search for answers. And of course one agent scrawled the secret message NO TRUST because you are not to be trusted.

And this happens to you, the player in the real world, because you trusted the game, thinking each restart was a reset, a blank canvas. But the canvas slowly begins to stain as you transform into a psychopath. The game knows.

The game knows.

SO THEN

Normally replays in branching narrative games deliver clean slates, giving players the power to map out the entire decision tree. Some hypertext games do retain memory between replays but it’s still a fairly rare occurrence which is why it surprises here. Some games do imply that “every attempt is real” such as suteF (Terra Lauterbach, 2010) but few developers go to the trouble of making those replays have tangible impact. The traditional replay is guilt-free because you’ve transcended the illusion of choice and embraced the system… but the trick played on the player here is rather clever.

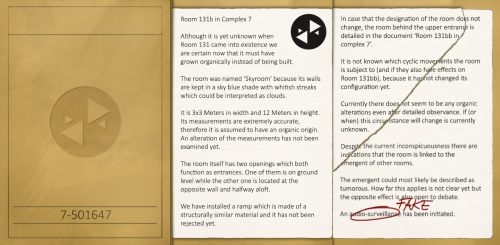

It becomes quite laborious to keep attacking the game’s decision tree and listen to the same responses from the agent over and over. I eventually quit because I’d had enough although the game remains ambiguous. It is not clear how the information gathered by agents relates to the prison the protagonist is implanted in. Whatever is going on, it’s definitely a little SCP-ish.

For players of Intra System: Trust Issues, I’ve included all the evidence I found below. If you’ve got more, please mail it to hm at electrondance.com and I’ll add it to this post.

Update 29 July: Rule 72. Almost certain the console does not want you to learn too much. In one scenario, the console ended communications and terminated the agent as he tried to reveal something. I also, er, got his arm broken when this happened.

Download my FREE eBook on the collapse of indie game prices an accessible and comprehensive explanation of what has happened to the market.

Sign up for the monthly Electron Dance Newsletter and follow on Twitter!

Basically I stopped reading when I got the hint that the game does something different on a replay, because that is my sort of jam.

I didn’t find the map that you found, so I guess I didn’t poke around quite as much and may dive back in.

This is also a spoiler, buuuuut:

I did find that in the one room where there “is nothing,” if you tell the Agent to look closely he sees a number on a display on the wall. The number starts at 0/4. Every time, it counts up. When it reaches 4/4, it just keeps repeating 4/4, as far as I can tell.

At 4/4, I’m not sure if it was because I did one dodgy thing earlier, but the Agent didn’t want to inject himself with the syringe. The first time I wasn’t able to convince him, but the second time I did. That seemed like a change from previous cycles.

OK, I actually found the map, and now it says 5/4. Nothing else though!

I should have realised you’d be all over this, Amanda. It’s funny you couldn’t get him to inject because that only just happened to me on the replay I did before posting this!

I found the numbers but I wasn’t sure what they implied. You might think it means you’ve got achievements, endings or found all the “collectibles” but 5/4 throws that theory out the window! Or does it? You got the map now it says 5?

When you feel like you’ve exhausted the game I’ll be interested in your response to the rest of the post. Even in last night’s replay I found something different giving me hope that I didn’t find everything…

HM, there’s no going back to the shadows.

I like the sound of this game and will probably give it a go. Normally, branching narratives are a bit of a negative for me. I feel compelled uncover all of the branches, as one might, but for me that somehow invalidates the experience. Which playthrough is the _real_ playthrough? I spuriously feel that my last playthrough has to be the canonical one. Even with simple naughty/nice morality choices, I still have a problem. For example, I find out that I can blow up Megaton and I want to see what that looks like – I have to abandon my neutral playthrough straight away and once I’ve learned to love the bomb, I will have to start again, unless I want this timeline to become _the_ timeline.

My Corvo was angry, grief-stricken, chaotic and violent. He passed that on to a young Emily. Who am I to change history? When given the chance, the blood of an older, wiser Corvo had cooled. Emily’s had not. But I could not go back. I couldn’t …lie!

The wonderful exception to this when there’s some diegetic explanation for trying out different branches. That’s why Life Is Strange really worked for me, and why I predict that I’ll not enjoy the non-time-travelling prequel quite as much. POP Sands of Time kind of did this in a way, with the “that’s not how it happened” reloads.

It’s not that I hate divergence – some of my recent favourites have had choices, branches or multiple endings, and have earned replays from me: Night in the Woods, Oxenfree, The Talos Principle.

But when there’s a diegetic reason for multiple story lines, suddenly many worlds are open and I can explore non-destructively. My play becomes about choices and consequences, cause and effect, rather than retelling the same story as it increasingly overwrites and invalidates itself.

Mr. Behemoth, welcome back. Especially as this is one of those posts I don’t expect much comment action on, something pretty fringe that got little traction.

If you’ve read the whole article already I’ve probably ruined most of the entertainment value for you, but I’m not going to stop you having a go. It does have issues– the game is sluggish and some of the dialogue strikes a false note. There is a tad too much “fuck” although I have heard the German narration is much better.

I don’t know if you were around the site at the time, but my magnum opus on choice and branching narrative is Stop Crying About Choice. I’m currently weighing up revisiting this which is why I haven’t made a reference to it in the post. It covers precisely this problem of choice vs knowledge, which is why Intra-System is very interesting for me, because it makes use this conundrum against the player. Few games try to incorporate the act of replaying into their framework because, frankly, only an absolutely crazy plot can make any sense of it. And just like using tests to justify being in a puzzle game (which Portal perfected) these few tricks to integrate the replay aspect into the game are finite and we’ll tire of them after a few yers.

I’ve got Oxenfree! I bought it just after it came out but it’s just not ended up on rotation. After spending a month or more on Prey, I feel like I haven’t been spending enough time on smaller sub-indie work like Intra System. Oxenfree will have its day…

Oxenfree is fantastic! Really it’s the voice acting that makes it, and the relationships between the characters, rather than anything particularly mind-blowing about the game design (though that’s perfectly good too).

Intra System, now, this game obviously drew some inspiration from Infocom’s 80s text classic Suspended, though judging from your description, HM, there may actually be less of a parallel than implied at a glance. Just reading your experiences and adding Amanda’s on makes the game seem incredibly intriguing and mysterious, not to mention sinister. Having agency with the Agent puts the player in a difficult position, especially when something as tantalizing as the truth is dangled in front of you for the low low price of mulching your way through a dozen of these nameless but free-willed proxies.

It’s funny, stuff that changes from game to game has existed as a concept forever; games in which changes remain, though, that’s relatively unique.

Steerpike is right about the acting in Oxenfree, and I’d also add it’s the way the dialogue system queues responses and sometimes interrupts when appropriate. It just flows well.

I’ve been around on and off since “Screw Your Walking Simulators”, so I just missed “Stop Crying…”. It looks like things that are already in my head, so I’ll read it properly later and try to get all the endings. A cursory glance reminded me of my intention to map out the recursive, kafka-esque phone menu of my local council and turn it into a surreal twine game. Maybe one day soon.

For an example of an ancient game with permanent consequences, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mesoamerican_ballgame#Human_sacrifice

I played this game last month and loved it. I wanted to uncover every one of its secrets, buuut… by the third playthrough I was so sick of the narrator repeating lines I’d heard twice before that I couldn’t go back.

I’m sorry, I know I should be more patient than this, but I badly badly need a skip feature if I’m ever going to get through this thing.

Steerpike

I get the Suspended reference, although I never played it more than a couple of turns as you need to full instructions to play and, at the time, I had just a pirated copy…! While Intra System does work similarly, in that your agency and senses are via a proxy, I’d say the guts of the two games are pretty different.

I’ve just had another stab based on a screenshot I didn’t recognise from my game. I’ve just confirmed one of my suspicions about the game!

Mr Behemoth

Oh that ball game is a permadeath game. Well, I guess in the real world, we’d just call it death. Now you’re making me think of Pyre… (a game I have not played)

James Patton

Yes, I think that is the big Achilles’ heel especially as there is no variation in the responses. The problem with all games that require fine combing of their decision trees. When I played Asemblance there was a similar issue.

If there were a skip feature, there’s also the possibility that the game’s ultimate secret wouldn’t work as well. I find it easier to play through again after taking a break. The few games I played this week weren’t as maddening.

I enjoyed this but stopped after two playthroughs. The repetition is a major drag factor as others have already said. The other reason is that… well, because I read about that lever staying broken after my first playthrough, I guessed where the game was going, and I had no desire to keep repeating and getting increasingly sociopathic about it. That is a problem with games like this. If you don’t want to be led down an increasingly dark path, ‘the only way to win is not to play’. Which is a sort of statement in itself, but not one you can particularly credit the game for.

I enjoyed the format, the concept, the first playthrough and the voice acting though. Solid work!

Shaun, if you read the spoilers I’m not sure the value of playing. In fact, I was originally going to talk about the problem of first time tension vs other time indifference, pointing out it is painfully tedious to go through all the same decisions again and again. So you don’t care.

It was only during the writing of that article did I realise something else was going on, that it had made me role play perfectly without force. However, I think most people might play once or twice but only a few will persevere much more than that.

I wasn’t clear: I played the game once, then came to read the article and read as far as “it remained broken in the next game”. And I thought, “oh! That’s cool!” So I played through a second time, and this time I had the agent do things I hadn’t asked for previously, but nothing which would make them come to harm. I got a slightly less positive ending.

And then I realised that to learn more I would have to really put this poor guy, with whom I had something of an empathetic bond, through the ringer. And I chose not to do that. Unfortunately this is not a choice the game offers, so it meant total disengagement.

So the point I was alluding to was: perhaps the game’s point is that to uncover ‘the truth’, or find ‘the full ending’, you must forgo any bond you feel with the agent despite the game working hard to construct it and you must treat them as nothing more than a game mechanic, or indulge in sociopathic glee.

And if that is the game’s point then there is some irony in the fact that a game purportedly about choice does not offer a choice concerning that reductive spiral toward cold methodical unpicking of its threads or delight in fictional suffering. If you reject that, for entirely valid ethical reasons either of your own or of whatever you imagine your character’s plight to be, then the only way to ‘win’ is not to play.

The game is certainly memorable for the fact of its tackling this theme and its iterative playthroughs sound memorable, but in terms of demanding the player monster themselves it is barely more sophisticated than Spec Ops: The Line’s white phosphorous moment or BioShock’s Andrew Ryan murder. 🙂

Okay I’m still gonna disagree, because you’re still looking at this from the point of view of being spoiled.

You get the credits if the agent makes it all the way to “your” room. That makes you feel the game is done. If the agent perishes, you don’t get the credits.

I’m sure Amanda had some research on this which would hopefully back me up. The first time people play, they play good. Once they feel they’ve “completed” the game, then the gloves come off. They don’t feel invested anymore and they toy with it more as a system.

But the game catches players doing this and remembers. Also, by being bad, it continually teases you with new information. Eg That room that was full of documents and the agent didn’t tell you what he found out? I know what he was reading about because I broke his arm. (oh my God, the evil cackling glee when I finally got him to tell me)

Going back to my original point, you already know there is a permanence across plays, so you’re acting accordingly – the game isn’t going to catch your hand in the cookie jar! But it’s not supposed to work like that. It’s supposed to catch you out.

I get the “no real choice but to be bad” association, but here it is trying to catch players out who think they’re just interrogating a system. It’s a clever joke on player behaviour – not a morality play. And that is what makes it highly unusual.

Okay, I think I see where you’re coming from. And I’d be interested in seeing the mentioned research.

I think my main point of contention with what you’re arguing is that, to me, the payoff for “interrogating the system” appears largely narrative (uncovering the mystery, seeing what happens to the agent character, further exploring the labyrinth). Which seems an odd contrast with the position that repeat play devolves into interrogating the system (though I realise on reading this back that I am conflating character and plot, perhaps because they are not story elements I would ordinarily prise apart).

I expect the main point of divergence for us might be that I very, very rarely play games role-playing as anything other than myself (by which I mean something to the effect of: I drive characters with my own sets of ethical principles and behavioural approaches, to the extent that any authored system will permit it) and so whether or not I knew of the spoilers, if I replayed for me this game would be ‘done’ as soon as I had exhausted the options I was comfortable with.

The underlying system is not of great interest to me. I may disagree with this later but for now I’m going to propose that is because no matter how cleverly constructed it is, it is still fundamentally a narrative delivery vector because its gameplay verbs are limited and its responsive stimuli largely narrative (I concede that discerning patterns and where they diverge is also a part of that set of stimuli). I’m also not suuuper into breaking down gameplay systems for fun or excessive replaying because to me that destroys ‘the magic’.

So this may just be a long-winded way of saying “horses for courses, innit”. Or indeed a long-winded way of saying I don’t get the joke, because the joke is not on me.

Here we go: In a study, over 1000 gamers were surveyed to see how the average player interacts with a game system that allows the player to choose a “good” or “evil” path through a game story. The finding was that the average gamer prefers to be good or heroic in such games. Gamers are most interested in exploring a character whose moral choices closely match to their own. However, those players that experience a game for the second time are then more likely to choose evil.

Oh, Shaun, we used to agree all the time. This is no good.

Excessive replaying that destroys the “magic” is something close to my heart also. It was going to be my main criticism of the game, that it is a decision tree that needs to be carefully explored again and again. But I stopped when I realised the narrative structure made sense even in this light.

I’ll just boil it down into what I read from this: typical player – play properly first, then play evil just to fool around. Game design integrates this player behaviour into the story. That’s it.

I’m not convinced my reading is 100% developer intention, I’m sure the plan was for players to gasp when they realised fooling around was being recorded. FALSE DECISIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES is right up there in lights – but it means consequences across games.

The “trust” thing seems more of a diversion. Like me, if you’re pretty good, this game is straightforward if you believe the console is telling you the truth. I think there’s a more potential here, a far more interesting game which really tests the relationship between the player and an NPC. (Intra-System is getting more content later in the year but I don’t think it will be this game.)

You’re worried about instantiating an evil version of yourself in role play; your priority was being you. I don’t think that’s what this game is really about, or even very good at, even though the trailer says it is. It’s more like Verde Station, Ethan Carter or Gone Home. It is a “story object” with the player as delivery mechanism. The game doesn’t make sense if play just one way.

(Critic’s Curse: If you were writing about this game for profit, you would have to be evil. How could you talk about such a short game knowledgably otherwise? That’s actually what made me do bad things when I wasn’t inclined to.)

I do not think this is an excellent game. I spent weeks wondering whether I should write about it or not. But it is definitely more than it seems at first glance and I have to give it a little clap for that.

I’m aware the deeper we go, the more likely we’ll contradict ourselves. (Critic’s Singularity.)

This is my article, for the research part: http://gamescriticism.org/articles/lange-1-1

The research is based on a survey largely distributed across gaming Reddits, so there’s certainly more scientific ways to gauge this. But generally speaking, it’s as HM says – gamers play good guy first, then bad guy second to see the rest of the content in the game. A few respondents to my survey seemed offended by the line of questioning I chose, I think because they thought I was trying to prove some agenda like “gamers are all sociopaths.” But in fact the opposite is true – my hypothesis was basically that gamers were sentimental wimps who don’t really like doing the evil path, and it was borne out in the data that I got.

I generally don’t worry too much about being a good guy on my first playthrough in a game, so I buck the norm. This particular game, I did play as nicely as I could for the first time through, though, which I found somewhat satisfying. I think the audio only method used in this game also does a really good job of letting you read the agent as a person, especially the first time through, because there’s no clunky visuals that might serve as a barrier to seeing him as a real person.

Thanks for the research links, both! Amanda, I have bookmarked your article and will read it in full soon.

(On the other points made: much food for thought, and I don’t have anything more to contribute at this time…)

I found out that if he showed you the Poster, you can Press a Red Button in the Settings. But just if you are still in game. I just saw it and Presses it at the end, as he wanted to put the Lever on Off.

Ps: I Asked Weltenbruch and he said to me, that there were a secret Ending, and it has something to do with a Poster. I think he means the Red Button.

Pps: He also told me as I got the Good Ending and than there was a 6/4 he agreed that this means how many different Ending you’ve got. I am Still looking for the ending, Good luck!

Justin,

Thank you for this insight! Yes, the red button does indeed pop up but only at ONE PARTICULAR POINT in the game. A little annoying I had to play through the game three times to explore the new decisions here. But I, too, now have 6/4. And once again, even though the game teases more knowledge at this point… it doesn’t really tell you anything.

Thank you again!

@Amanda, I finally made the time to read your research article, and I’m glad I did. It was really interesting. Previously my only reference points for understanding where my decisions lay in relation to other people was in the form of the “X% of people made Y choice” screens at the end of Telltale games. I had no idea that the majority of people effectively played as I did (except I don’t tend to do second playthroughs, because life is short and games are many). I’ll be thinking all of this over for a while.

Scattered thoughts:

(1) Looking back at what I wrote above, I’m wondering about the attitude I was expressing being self-limiting. Perhaps I’ll experiment a bit more. Be more of a bastard. But on the other hand, what is the outcome of that? Unless games genuinely offer unbalanced extrinsic reward for it, the reward is, I guess, the frisson of excitement about transgression? I don’t know.

(2) Anecdotally: my first Mass Effect trilogy playthrough was “good”. My second was too! But the latter was also my “canonical” playthrough as it included all the DLC, and the games were played back to back. Maybe there’s something to the idea that players want a certain playthrough to be their “official” one, and in others they’re just playing with toys. That feels like it meshes with players who run through games like the Walking Dead only once, because for better or worse whatever happened is “their story”, which is only undermined by revisiting the game.

(3) I’m glad that New Vegas and Dragon Age were called out for having more faction- or background-based moral systems. Limited as they were I think they’re more interesting and offer a lot more space for exploring these ideas.

(4) The notes about railroading players in narrative games without offering them an out is something to mull over. Offering too many branching options is expensive, and allowing certain options could shut off the ‘critical path’ – but if you don’t offer people the option they don’t like it. It’s as true if they are “omniscient” (have played before) or have just picked up on subtler details, or made what they regard as a mistake and want to “get out”.

(5) The anecdote about Spec Ops the Line after “hide the heroic option” – I really liked that moment. I panicked for a second or two, noticing I was being hurt, and then I myself shot in the air and the mob scattered. Great moment, much better than the White Phosphorous scene.

(6) “…a future of more nuanced choices may point to a stronger direction for the medium. If gamers are not interested in being evil, we can get more traction by instead questioning what they believe to be good.” It’s this, as well as acknowledging that moral systems are a social construct rooted in various specificities, that I kept returning to as I read this essay. It’s an area I think I’d like to explore if I ever make the time to start making my own daft little games.

(Hey, thanks for offering this awesome forum @Joel! It’s nice that you do articles on it too)

I had to do some sleuthing of my own, but I finally found the story this reminded me of: https://web.archive.org/web/20110824030340/http://www.lifestartshere.net:80/2010/04/hell.html

Now that it’s a few months later, did you ever figure out what’s what with the game? Your starseed spoliers are what brought me here – sometimes it’s nice letting you solve all the the hard videogame mysteries for the rest of us.

Dan – you’re going to have to give me some time to read that 🙂 However, first, I’m just getting the 4th episode of Side by Side ready for tomorrow…

Right so, yes, I can see why that Intra-System jogged your memory of that story.

I think I have all the information in the game but it doesn’t add up to anything concrete. Some of the most important information is only revealed through deliberately bad choices but… I don’t think there’s anything concrete here. To let slip some insider knowledge, the Smoke Some Frogs team did tell me over e-mail that the story was deliberately ambiguous. I think it’s more ambiguous than I was expecting.

Like it seems difficult to piece anything together, as if we’re missing a lot of information. Does that map tell me anything? Does it even relate to the rooms the agent is passing through? Do the names of the mannequins tell you anything? And so on and on.

Although I did get something out of the exercise, I don’t think it’s possible to reach narrative satisfaction. However, I hear the team is planning some “DLC”…