In 2012, Jenn Frank wrote about how she rediscovered some floppy disks carrying some of her Norn creations from the artificial life simulation Creatures (Millennium Interactive, 1996). She saw them as coffins. She sent her Norns into stasis on floppy disks but they never woke up; she had murdered her brood.

Save games. A thorny subject for sure. In 1981, we might have asked whether a man was not entitled to the control of his own leisure time. ‘No!’ said the developer from his office cubicle. But we are not in 1981 any more. In 2014, I should be able to do anything I want, whenever I want, with whomever I want, multiple times. Not only can I do whatever I want but I can also shout at people on the internet for doing whatever they want. This is liberty.

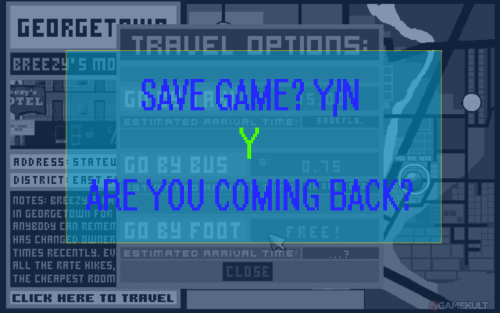

The save game is one of the most important innovations in game design. It’s also a promise to the developer that we’re coming back.

But why do we sometimes break that promise?

Let’s talk about glitch. Glitch is chic right now. Glitch is a cooler word for bugs, which means bugs are cool, provided you call them glitches. Over the last few years, we have seen games that appropriate bugs, I mean glitches, as a component of game design. Many of these are glitches by design so according to a, well, precise definition, a glitch programmed on purpose cannot be a glitch at all. So being glitchy is a style, a fashion.

Fjords (Kyle Reimergartin, 2013) is glitchy. It’s also part of the Sharecart 1001, a package of games that all share the same save file. I never even heard of the Sharecart idea before I played Fjords. What happened is that I read some words boasting that Fjords was marvellous and then I saw a trailer and then I thought I really want to see this crazy de jour.

Fjords resembles explorer-platformers from the 80s and is complete with all sorts of “bugs”. If you fall off the bottom of the screen, you might end up somewhere unexpected. Every time the player uses the warp ability, small pieces of lethal, twisted reality will remain and clog up the screen. It’s similar to games like You Say Jump I Say How High (Pippin Barr, 2012) where the player can only make progress by controlling the parameters of the game: in Fjords, the player is expected to “reconfigure” the game reality to get about. Fjords is also a bit Inception as there are worlds within worlds within worlds.

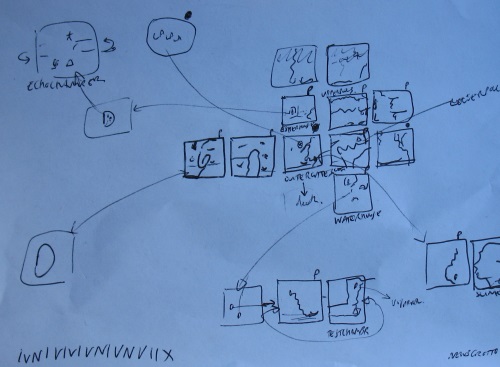

I found Fjords hard work – coming up with the right reality configuration to go from A to B was not always straightforward. I decided I had to scribble down a map to keep track of progress. The glitchy theme meant there could be secrets hidden everywhere. I saved my progress and quit so I could work on a “formal” play session later.

Weeks went by.

Corrypt (Michael Brough, 2012) played out a similar way. It starts off like a claustrophobic Sokoban clone with some entertaining puzzles and then the world glitches. I’m going to have to spoil something for you, here. A single block of the world is distorted, glitched permanently, even if you move from room to room. That’s certainly interesting but what freaked me out was the game’s next move: it gave me the power to glitch what I wanted.

It felt like I needed to solve all of the puzzles at the same time. It blew me away. Fuck me, this is the next level, I thought. I exclaimed on Twitter “Oh my God, @smestorp #corrypt”.

I couldn’t just potter around any more, I had to take it seriously. I quit the game, intending to return to my saved game later, when I was ready for its challenge.

It is a year on and the Corrypt shortcut in the corner of my desktop has not been clicked since.

I’ve also previously written about how I abandoned my avatar Gwaul in Mount & Blade (TaleWorlds Entertainment, 2008). The character who I’d invested many hours in had painted herself into a political corner and her story had become unplayable. The save game was her grave.

This can even happen in an FPS. I tell myself every time not to save the game before a difficult battle – save the game before an easy, exploratory section. Something with puppies and flowers. That’s a proper save point, you know. But I just can’t help myself. I keep playing through the puppies and flowers and it’s always the challenge that interferes with progress, the challenge that dictates when I stop playing. It’s dangerous because I associate the memory of a hard struggle with the game. Sometimes I can’t face opening the game again because it doesn’t sound like fun. Like when I played Zeno Clash (ACE Team, 2009) but realised I was pretty bad at the melee combat. I’ll come back to this later, I lied to myself, when I’m not so tired.

If kids demand games that take ten or more hours to play, the save game is essential. But it has another role, too. It allows us self-deceit. It allows us to quit without having to make the decision to quit.

Some of us complete every game we download. Some of us grow up. Not every game is deserving of completion. Not every game is suited for our particular personality type. If I’m grinding in a game for too long, I find it difficult to return to. That’s probably a good thing. If you’re looking for the definition of a game, you won’t find that motherfucker under “grind”.

But for every self-deception there’s also a nefarious self-deception-deception. I get depressed every time someone gives up on Cart Life (Richard Hofmeier, 2011) because they say it’s depressing. Every time someone tweets that, an angel gets their wings cleaved off with a blunt spoon smothered in chilli. “I gave up on Schindler’s List because it was a fucking downer with all those Jews getting killed. Why would I watch that?”

You’re never short of experience. Twitter is full of experience every single minute. And every day, new games are being published, many cheap and many free. There’s no excuse not to be experiencing something. The save game gives us pause and escape. But it’s also easy on us. Perhaps it takes more guts than we admit to follow through on a game. There are always choices. We all love choice, don’t we? Choice is the fuck. Infinite monkeys on infinite controllers. Someone out there is playing the perfect game and it isn’t me. I should play something else. I am playing something else.

I finished Fjords. I drew a little map and the game ended more quickly that I expected. I enjoyed working through it but the ending was tinged with relief. Fjords has so many little secrets and, as it makes you work for them, I knew I hadn’t seen everything. Just thinking about collecting every piece of pizza made me feel nauseous. I’d done enough. It was good enough. Look, it’s okay for a game to remain unknowable after completion. Shhh. Hush now. Hush.

I don’t want to educate people into believing they have to finish games. But I don’t want people to walk out on Schindler’s List or put down Atonement halfway through. No, screw that. Atonement was a tedious asshole of a book. I read a third of Atonement on the commute and put that piece of shit down for two years. Then I forced myself to finish it, expecting to realise it was all worth it. It was not all worth it and your long flowery sentences wasted my time, Ian McEwan. Never use twenty-seven words when one will do, Ian McEwan. Hush now.

In a world where designers are exploiting human psychology to make games more addictive, the save game is the only friend we have. We need friends in a world like this. It’s a war zone out there. We decided to give up paying for games so the developers took the war to our wallets. Maybe the save game is a way to save games. Obi-Wan, it’s our only hope.

I don’t know how to end this article. Are save games vital or do they take away a game’s sharp bite when it demands a little spunk? I don’t know. I need to think about it a bit more.

Think I’ll save this document and come back to it tomorrow.

Download my FREE eBook on the collapse of indie game prices an accessible and comprehensive explanation of what has happened to the market.

Sign up for the monthly Electron Dance Newsletter and follow on Twitter!

Great read. This is what I tell myself: I will complete the games that I am meant to complete before I die. If I die first, I’m not missing anything.

It’s somewhat extreme and requires some belief in “meaning,” but it’s also simple and effective for making me feel good about what I’m playing (or not playing).

I love the idea that the save game gives us an out. I have a tendency to think of games (and all artworks) as “finished pieces”, as things that you can be sure the player has played through in its entirety. It’s helpful to be reminded that a game not played to completion isn’t just an anomaly one has to take into account when thinking about games – it’s often the norm.

Some thoughts:

Schindler’s List may be tough to watch but I don’t think many people would stop watching halfway through. There’s something about film that invites you to just keep watching – it’ll keep rolling on its own. But pushing through a game can take effort. Does that mean playing Schindler’s List: The Game would be more harrowing or somehow more “worthy” than watching Schindler’s List: The Film? Is there anything to be said for the effort you have to expend to get to the end of Planescape: Torment or Cart Life or Infinite Jest or Moby Dick, which you simply don’t need to sit through even a two-and-a-half hour film?

My girlfriend says that nobody would stop watching Schindler’s List because they were depressed; instead, they would stop watching because it might be too slow to engage people of our generation. She says this makes her sound horribly shallow but she’s not, really.

I know this wasn’t your focus, but your “are save games a good or bad thing” ending put me in mind of how save games are not just bookmarks – they can also be used by the player to explore the game along multiple timelines. Rather than using save games to play linearly along a fixed narrative, you can use them to sort of map the game outwards.

Ian McEwan is a horribly overrated author. There isn’t a single book of his that I actually liked.

@Jed: Thanks for your first comment on the site! I often worry that save-as-suicide means I’m quitting games that I shouldn’t. I’m pretty sure I’ll congratulate myself for getting through Corrypt but right now I’m left the hurdle of actually clicking the shortcut. It seems like an insurmountable problem.

@James: I have an even more hazy perspective than yours. I think we’re moving into a phase where “completed” is undefined for most games; think in terms of achievements or secrets, all the side missions in GTA. When are you really done any more? Just when you’ve seen a closing cutscene?

My Schindler’s List point is really to highlight the absurdity. By placing a save point in the middle of Schindler’s List and allowing the audience to go away for a week – how many would come back? This happens to some TV watching right now with PVRs and the like; programmes go on permanent pause until, six months later, you realise you’re not going to watch the rest of it.

The length of many modern games means that this break is not merely a convenience, but makes the game a feasible experience. But it also means the our appreciation of the message or plot of a particular game is undermined by having this break. I’m also having problems expecting ten hours of gameplay to deliver some sort of narrative power which is superior to the condensed format of film or television. This is a slightly more complex discussion, though, the whole story/gameplay angle. I just wanted to drive at the idea that the save game will allow us to quit early… and who knows how much good stuff we would have missed out on.

Maybe the evolution of the save game will be to checkpoint process and tell the player “right, you have to stop here now, this is your cliffhanger, come back in a couple of days and we can go forward”.

The original seed for this essay was that puzzle games, which are marathons not sprints and expect you to go away and have a think, are susceptible to losing users during a save. I realised the issue was probably larger than just puzzle games and here we are.

As for the multiple timeline aspect of save games… well, watch this space.

Saves also have the benefit of encouraging players to, uhh, suicide. Or, if I wanna phrase it properly, saves allow them to “pursue behaviours that the game would otherwise punish”.

Think smashing cities in SimCity, or making an initial mad-dash through a dungeon in Skyrim, or pursuing batshit crazy dialogue choices in Fallout 3, or the police chases/city-wide shoot-outs that happen when players goad the cops in GTA. It also turns up a lot in Visual Novels, but we can safely ignore them. Because, everyone ignores them.

Enjoyed this read, HM. I completely agree about the psychology of save points and the excuses we make to ourselves. My movement away from the attitude of ‘I have to finish this game!’ is very slow, despite my backlog at this point probably being impossible to complete in two years of dedicated full-time effort.

Back in the day, when I used to be terrified of taking another step in Quake 2 or Unreal, I would often save and then make a mad dash through an area with guns blazing. Ordinarily I was a very cautious and gradual play, conserving ammo and trying to tackle enemies piecemeal, but knowing that I had a specific save to fall back on encouraged me to push aside my nerves and pursue a gung-ho approach. Over time it also proved that such an approach is often more successful than treading lightly.

The game where that fell down was Rebellion’s original AvP, but that’s another story.

Anyway, I have a sizeable archive of saved games. I don’t just leave them with an installed game, or let them remain when I uninstall a game – I’ll often stuff them into ZIP or RAR archives, telling myself it’s for later use. The screenshot I’ve uploaded below may indicate just how absurd an idea that often is.

http://imgur.com/eKcPr9J

(Nb. a few of those archives contain saves for games I’ve finished but love, or have enough invested in a character that I didn’t wish to ‘let them go’ by erasing the saves.)

Incidentally, McEwan is a bit of a pompous bore but I remember finding his collection of sex/kink short stories In Between the Sheets a compelling read.

Shaun: that saves archive is amazing! And it looks like it goes back to 2000 in some places. That seems like a staggering amount of time to archive things for (although I’m not the most organised person in the world). I’m interested in this idea that by deleting these saves you would be saying goodbye to a character or, even, killing them.

My attitude to saved games is very different: in my teens I played and replayed games so often that I had no attachment to particular save files at all. Whenever I formatted my hard drive (every few years) I would make almost no effort to preserve saved games, my logic being I could just play through the game from scratch and get to the same point if I wanted it so badly. When you’ve completed the Red Alert 2 singleplayer campaign three times, the idea of keeping that most recent RA2 saved game seems silly – it’s more like a bookmark than a character.

The biggest exception to this is RPGs. I remember when I played Neverwinter Nights I had one character whose journey I was more invested in than most. While I was playing through the official campaign I decided to change his character from a straight sorceror to a dragon mage (I think – these terms are all very foggy to me now), and I decided to change his surname between expansion packs to reflect this. That’s the only save game I’d consider keeping for good, because his story changed for me in unexpected ways.

The only other one I’d be tempted to keep would be my Mass Effect 2/3 saves, because I had such a strong connection with my Shepard. But those games are so plot-driven – the focus is always on moving Shepard forward towards the conclusion of his/her story – that I don’t see any reason to go back. What I do instead is I tell other people about The Tragedy of James’ Shepard: she made a poor decision out of over-confidence and hubris, which got someone killed, which got *an entire species killed*. It’s interesting to me that I have no desire to go back to that Shepard, but I’ll talk about her if she comes up in conversation. Part of the reason is that this was a big learning experience for me: making that terrible decision showed me what *not* to do in real life, so Shepard’s journey was, for me, a way of learning that lesson. Now that I’ve learned it I don’t need to return to her.

James: it does go back a fair way, although some of those saves never get loaded. I have various reasons for keeping them, ranging from “I just back everything up and don’t tend to delete stuff of negligible file size” to really game-specific stuff. For example, the saves from 2000 for Albion (Blue Byte’s excellent if confused RPG) are probably from a game where I took every character to the level cap. I either kept the saves as a memento of that, or because I might one day have attempted to defeat the final boss in the ‘unconventional’ manner (which I think involves 1,500 casts of a single spell, rather than just using the plot macguffin like you’re supposed to) and having a fully-levelled team ‘made sense’ for such a monumentally idiotic task.

Diablo 2, on the other hand, I have no reason to keep. I played the game for about eight hours solo and reached a point where progression was extremely difficult. I think backing up the saves was my way of justifying giving up whilst circumventing the sunk cost fallacy.

I have no idea why I saved e.g. Fate of Atlantis saves. I finished that game and although it’s not entirely linear, the divergence is about the journey.

I would like to add that Shaun is not the only member here of the Cult of the Savegame Archive. I have Deus Ex saves, NOLF saves, GTA III saves… looking back at the dates, seems that 2003 was the big year this all kicked off.